I got my first diecast fifty years ago. My mother and father must have thought that at six years old I was ‘grown-up’ enough to have a real toy at last, and so Christmas morning 1958 saw me tearing open the brown paper packaging (potato-printed with holly and what could have been reindeer, although they looked rather like our bull-terrier wearing a T.V. aerial. My father’s wages as a long-distance lorry driver didn’t run to shop-bought wrapping) to reveal a magically reduced version of his Foden eight-wheeler. Every detail was there, from the door handle at the rear of the cab to the hole under the radiator for the starting handle. I could imagine myself cranking the engine over, thumb tucked away in case of a kickback just like Dad and watching the cab rattle into life.

I got my first diecast fifty years ago. My mother and father must have thought that at six years old I was ‘grown-up’ enough to have a real toy at last, and so Christmas morning 1958 saw me tearing open the brown paper packaging (potato-printed with holly and what could have been reindeer, although they looked rather like our bull-terrier wearing a T.V. aerial. My father’s wages as a long-distance lorry driver didn’t run to shop-bought wrapping) to reveal a magically reduced version of his Foden eight-wheeler. Every detail was there, from the door handle at the rear of the cab to the hole under the radiator for the starting handle. I could imagine myself cranking the engine over, thumb tucked away in case of a kickback just like Dad and watching the cab rattle into life.

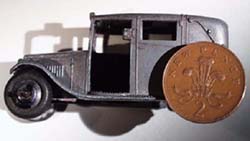

It was realistic, it was beautifully enamelled and it was solid, three of the qualities that have made die-cast toys such durable attractions for the collector. So much for their magic, but what actually do we mean by ‘die-casts’ as opposed to any other kind of metal toy? Die-casting as an industrial process came into being towards the end of the First World War. Casting itself is as old as metalworking, it simply means pouring molten metal into a mould from which the final object is shaped. In the early years of the twentieth century several American manufacturers began ‘slush casting’ model car bodies in cast iron. A wooden ‘form’ of the model was pressed into moist sand to create a one-shot mould into which molten metal was poured. As the metal in contact with the sand solidified the remainder was tipped out to leave a hollow casting, in terms of thickness and quality rather like a chocolate Easter egg. Next in complexity came ‘hollowcasting’ famous for producing lead soldiers, in which liquid metal is poured into a two part mould and swilled out to leave a hollow shell. Finally in die-casting as we understand it the molten metal is forced under pressure into a die, a two or more part metal negative of the finished model. As soon as the casting has cooled to its solid state the die is opened and the basis of the finished model falls out. This process allows almost ‘hairline’ detail to be incorporated into the surface of the toy, a great improvement on the tin-plate it superseded.

It was realistic, it was beautifully enamelled and it was solid, three of the qualities that have made die-cast toys such durable attractions for the collector. So much for their magic, but what actually do we mean by ‘die-casts’ as opposed to any other kind of metal toy? Die-casting as an industrial process came into being towards the end of the First World War. Casting itself is as old as metalworking, it simply means pouring molten metal into a mould from which the final object is shaped. In the early years of the twentieth century several American manufacturers began ‘slush casting’ model car bodies in cast iron. A wooden ‘form’ of the model was pressed into moist sand to create a one-shot mould into which molten metal was poured. As the metal in contact with the sand solidified the remainder was tipped out to leave a hollow casting, in terms of thickness and quality rather like a chocolate Easter egg. Next in complexity came ‘hollowcasting’ famous for producing lead soldiers, in which liquid metal is poured into a two part mould and swilled out to leave a hollow shell. Finally in die-casting as we understand it the molten metal is forced under pressure into a die, a two or more part metal negative of the finished model. As soon as the casting has cooled to its solid state the die is opened and the basis of the finished model falls out. This process allows almost ‘hairline’ detail to be incorporated into the surface of the toy, a great improvement on the tin-plate it superseded.

Tin-plate toys had been constructed from stamped and cut pieces of sheet metal bent into shape and clipped or soldered together by hand. The impression of detail – door handles, bonnet louvres etc. was given by using lithography to print pictures of the required components on to the tin, but the detail remained two-dimensional, it was left to die-casting to bring its depth to life. So the increasingly mechanised world which followed the Great War had discovered a way to produce toys of an accuracy and robustness far superior to that of tin plate.

Tin-plate toys had been constructed from stamped and cut pieces of sheet metal bent into shape and clipped or soldered together by hand. The impression of detail – door handles, bonnet louvres etc. was given by using lithography to print pictures of the required components on to the tin, but the detail remained two-dimensional, it was left to die-casting to bring its depth to life. So the increasingly mechanised world which followed the Great War had discovered a way to produce toys of an accuracy and robustness far superior to that of tin plate.

The only real drawback was the cost of making the die for each new model. Die making was a process requiring great engineering skill, beginning with the hand crafting of a wooden mock-up, perfect to the tiniest detail, of the finished toy. The really fine work, door lines, radiator grilles etc. could be added with wire, the delicacy of this limited only by the ability of the metal used to flow successfully into the smallest crevices of the mould. The preferred metal for die casting toys is ‘mazak’ or ‘zamak’ if you are American. Basically it’s zinc with 3-4% aluminium and 1-2% copper added. Some of the earliest casting used lead, but as toy sucking lead to brain-damage it rapidly fell into disrepute. (These early lead toys were very expensive and so sucked only by the c hildren of the privileged classes, who grew up to run our society. Draw your own conclusions.)

The slightest contamination of this mixture causes that bane of early die-cast collectors, fatigue.  When first manufactured no one could have foreseen the problems this would cause. A toy’s life was, if fortunate, measured in years not the decades, which the collector’s market has extended it to.

When first manufactured no one could have foreseen the problems this would cause. A toy’s life was, if fortunate, measured in years not the decades, which the collector’s market has extended it to.  Fatigue is the name we give to the process of granularisation which causes the metal of a model to deform and eventually disintegrate. There is as far as I know very little to be done to cure this, the best advice seems to be to avoid handling the model and keep it room temperature. Not all parts of a model suffer fatigue at the same rate; cast wheels seem to be particularly prone.

Fatigue is the name we give to the process of granularisation which causes the metal of a model to deform and eventually disintegrate. There is as far as I know very little to be done to cure this, the best advice seems to be to avoid handling the model and keep it room temperature. Not all parts of a model suffer fatigue at the same rate; cast wheels seem to be particularly prone.

The theory seems to be that as wheels are relatively crude castings the same attention to detail in mixing the metal was not always given compared to that lavished on metal that had to flow into very finely detailed moulds. To keep the mould simple the toys are often made from two castings, in the case of my Foden one for the cab and chassis unit and one for the body. Before joining together each casting was tumbled in a rubber-lined drum part filled with loose stones and soapy water to remove any ‘flash’, the unwanted residue of the casting process. Next came a chemical preparation to help the enamel bond to the metal, and then the paint itself would be applied by spray gun as the models rotated along a conveyor belt to the ovens. Baked on at 200 degrees Centigrade the finish is extremely durable, another advantage for a roughly treated toy. Detail work, lights and radiator grilles etc., was hand sprayed through masks before the final assembly was completed with either screws or rivets.  Among the first people to exploit this new technology for the toy market were the Dowst brothers of Chicago. They brought out their first “Tootsietoys” in the early 1920. Unlike tin-plate these new toys could faithfully reproduce the complex curves of full size automobiles, and were soon being used by motor dealers to promote their wares. Scaled to 1/43rd of their real counterparts Tootsietoys set a standard which was soon followed across the Atlantic by that colossus of the British toy industry Frank Hornby.

Among the first people to exploit this new technology for the toy market were the Dowst brothers of Chicago. They brought out their first “Tootsietoys” in the early 1920. Unlike tin-plate these new toys could faithfully reproduce the complex curves of full size automobiles, and were soon being used by motor dealers to promote their wares. Scaled to 1/43rd of their real counterparts Tootsietoys set a standard which was soon followed across the Atlantic by that colossus of the British toy industry Frank Hornby.

Hornby had begun to manufacture his ‘Meccano’ construction system in 1900, and by 1918 had added model railways to his repetoire. To increase their trackside realism he introduced sets of sheep and cows and in 1933 the first ‘Modelled Miniatures’ were announced in the December issue of the Meccano Magazine. They first group consisted of a tank, a tractor (modelled on the Fordson of the period), a sports coupe, a motor truck, a delivery van and an open sports car. Hornby’s copywriters stressed the ‘ realistic moulding’ of the new toys, even down to the rivets on the armour of the tank. They were an immediate success and with the addition of new models in April of the following year they were given their more familiar name of Meccano Dinky Toys. The word ‘Dinky’, meaning small, was like Hornby himself of Scottish descent. A second factory was opened in Bobigny, France, to complement the original in Liverpool with French dinkies becoming regular imports to Britain and vice-versa. Not that France suffered any lack of die-cast toys.

Citroen had used 1/43rd scale models to promote its 1928 range at car shows, and four years earlier M. Ferdinand De Vazeills had expanded his industrial die-casting business to include toys. Renowned for their robustness this ‘Solido’ brand became one of the most innovative, introducing among other features, opening doors and sprung wheels. In England Dinky had the market pretty much to themselves throughout the thirties and forties until Playcraft arrived on the scene in 1956 with their ‘Corgi’ brand, similar in scale and quality but featuring plastic windows for the first time. That so much survives from this golden age of die-cast toys is a tribute to the engineering, strength and integrity of these tiny models. Solido once boasted that it’s toys were strong enough to double as roller skates, and to my embarrassment that was the ultimate fate of my Foden chain wagon, deprived of it’s chain posts and bound to my boots with rubber bands it joined a Guy flatbed as my first pair of skates, but it survived the rigours of our back yard to take its place as the most battered (or should we say ‘patinated’) star of my collection.

Die-Cast Information & Features